Ultra HD Video

4 hours 25 minutes

2024

“Blood, bile, intracellular fluid; a small ocean swallowed, a wild wetland in our gut; rivulets forsaken making their way from our insides to out, from watery womb to watery world: we are bodies of water.” Astrida Neimanis

The human body is not discrete or individual, it is not sealed and defined; it is sponge like and weeping, it exists intermingled and reliant on other matter. Cultural theorist Astrida Neimanis speaks of the myth of individualism, of how one's body is “multiscalar and multigenerational; porous and palimpsestic…it is never only one thing, in only one place, or only ‘itself’”. Through this we recognise that the delineation of membranes are complex, that we must ponder how to locate oneself amongst a sea of other matter. We are planetary bodies.

Biologically the body is watery, flowing with intracellular and extracellular fluids. It is fed by rains, rivers and tides. It secretes and absorbs, replenishing itself before leaking once again. We are in constant exchange with our environment, physical, cultural and geopolitical, storing the histories of the water we ingest. Our brains, bones and organs are all watery flesh, a continuous flow that endures even once burned or buried within the earth. A hydrological cycle unto itself.

One year ago my body became part of its own hydrological cycle while birthing a child; followed closely by a placenta. I leaked amniotic fluids and plasma. I became part of generations of people whose bodies circulated through birth and death in minutes, the arrival of a vernix coated baby and the discarding of a now lifeless temporary organ. Over forty litres of blood per hour passes through the placenta to support life in utero, over fifty percent water. Whatever the mother ingests; food, liquid, medication, pollution, social unrest, disease, flows through the placenta. It filters and pumps life, a womb connected to its environment.

All human and non-human bodies are entangled to this watery planet through a fluid continuum. Our aqueous imaginary must no longer perceive water as ‘out there’, it is definitively close, it binds us and holds us, it makes bodies and networks and ecologies proliferate.

The human body is not discrete or individual, it is not sealed and defined; it is sponge like and weeping, it exists intermingled and reliant on other matter. Cultural theorist Astrida Neimanis speaks of the myth of individualism, of how one's body is “multiscalar and multigenerational; porous and palimpsestic…it is never only one thing, in only one place, or only ‘itself’”. Through this we recognise that the delineation of membranes are complex, that we must ponder how to locate oneself amongst a sea of other matter. We are planetary bodies.

Biologically the body is watery, flowing with intracellular and extracellular fluids. It is fed by rains, rivers and tides. It secretes and absorbs, replenishing itself before leaking once again. We are in constant exchange with our environment, physical, cultural and geopolitical, storing the histories of the water we ingest. Our brains, bones and organs are all watery flesh, a continuous flow that endures even once burned or buried within the earth. A hydrological cycle unto itself.

One year ago my body became part of its own hydrological cycle while birthing a child; followed closely by a placenta. I leaked amniotic fluids and plasma. I became part of generations of people whose bodies circulated through birth and death in minutes, the arrival of a vernix coated baby and the discarding of a now lifeless temporary organ. Over forty litres of blood per hour passes through the placenta to support life in utero, over fifty percent water. Whatever the mother ingests; food, liquid, medication, pollution, social unrest, disease, flows through the placenta. It filters and pumps life, a womb connected to its environment.

All human and non-human bodies are entangled to this watery planet through a fluid continuum. Our aqueous imaginary must no longer perceive water as ‘out there’, it is definitively close, it binds us and holds us, it makes bodies and networks and ecologies proliferate.

With thanks to my kin Ida for bringing this story into my world and offering me a way of understanding my own body as part of a planetary whole. To my partner Wilson for sharing this journey with me.

Edit and sound design: Wilson Bambrick

Platform Arts, Geelong. January - February 2024

Edit and sound design: Wilson Bambrick

Platform Arts, Geelong. January - February 2024

Installation

2022

Channel is an installation that acknowledges the Birrarung (Yarra River) as a living entity and highlights the value of water as central to ecological survival.

Water embodies all survival, as flow, eddy and stream. Water channels through our blood and underneath our cities, as monument, politics and breath. In the same moment we are both within, and composed of, bodies of water. We are as interconnected to the river systems as we are reliant on the ocean's current. We are as bound to water as the dry soil beneath our feet. It is through this lens that Channel comes to life.

Channel acknowledges the Birrarung (Yarra River) as a living entity and highlights the value of water as central to ecological survival. Since colonisation the development of cities have shaped new landscapes, carved up ecosystems and eradicated natural flows. Drought and flood have increased in severity and habitats destroyed. In a time of climate emergency it is imperative that the value of water is renegotiated, where culture and nature no longer collide.

Channel is a temporary installation that casts light onto the effects of stormwater pollution in river systems. Highly contaminated urban runoff is channeled into the river from the Elizabeth Street main drain, once a thriving waterway known as William’s Creek. One of the most affected stormwater drain outlets in Melbourne, this runoff is one of the largest contributor to pollution in the Lower Yarra catchment and disturbs habitats within the river and further downstream into the bay. As a live testing site Channel siphons water from this polluted point and treats it through natural processes. The large tank holds approximately 1300L of stormwater from the river below, containing many residual pollutants as a result of urbanisation. The water is being treated by microscopic insects, aquatic snails, endemic plants and macrophytes as well as charcoal created from timber found in the local Bandalong litter traps. These organic materials will help to increase oxygen levels and neutralise impurities before returning it to the river at the completion of the work.

Water, as a living entity in its own right, supports multiple life forms and needs to be reimagined within the context of colonised urban networks. As Donna Haraway so aptly comments “Our task is to make trouble, to stir up potent response to devastating events, as well as to settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places.”

Water embodies all survival, as flow, eddy and stream. Water channels through our blood and underneath our cities, as monument, politics and breath. In the same moment we are both within, and composed of, bodies of water. We are as interconnected to the river systems as we are reliant on the ocean's current. We are as bound to water as the dry soil beneath our feet. It is through this lens that Channel comes to life.

Channel acknowledges the Birrarung (Yarra River) as a living entity and highlights the value of water as central to ecological survival. Since colonisation the development of cities have shaped new landscapes, carved up ecosystems and eradicated natural flows. Drought and flood have increased in severity and habitats destroyed. In a time of climate emergency it is imperative that the value of water is renegotiated, where culture and nature no longer collide.

Channel is a temporary installation that casts light onto the effects of stormwater pollution in river systems. Highly contaminated urban runoff is channeled into the river from the Elizabeth Street main drain, once a thriving waterway known as William’s Creek. One of the most affected stormwater drain outlets in Melbourne, this runoff is one of the largest contributor to pollution in the Lower Yarra catchment and disturbs habitats within the river and further downstream into the bay. As a live testing site Channel siphons water from this polluted point and treats it through natural processes. The large tank holds approximately 1300L of stormwater from the river below, containing many residual pollutants as a result of urbanisation. The water is being treated by microscopic insects, aquatic snails, endemic plants and macrophytes as well as charcoal created from timber found in the local Bandalong litter traps. These organic materials will help to increase oxygen levels and neutralise impurities before returning it to the river at the completion of the work.

Water, as a living entity in its own right, supports multiple life forms and needs to be reimagined within the context of colonised urban networks. As Donna Haraway so aptly comments “Our task is to make trouble, to stir up potent response to devastating events, as well as to settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places.”

This project is co-produced by the City of Melbourne and Testing Grounds, and curated by Arie Rain Glorie as part of Test Sites Phase 2. Channel is presented as part of ACCA’s (The Australian Centre of Contemporary Art) program Who’s Afraid of Public Space, which explores the role of public culture, the contested nature of public space, and the character and composition of public life.

With thanks to The Science Gallery, Australian Ecosystems, Light Projects, Dr. Peter Breen, Bob Sowter, Ky Starcevich, Domenica Wenban and Wilson Bambrick.

This project acknowledges the Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation, on whose unceded land the Birrarung flows. This project acknowledges them as Traditional Owners of the land and waterways of this Country, and pays respect to Elders, past present and emerging.

A trace object from this project is also presented here [Untitled].

Images courtesy of the artist, Aaron Claringbold and Peter Tarasiuk

Media Link:

Australian Centre of Contemporary Art (ACCA)

Hyperlocal News

Sculpture

Sump oil, water

2022

A trace object from Channel is presented at ACCA over the duration of the exhibition. From extraction processes to post-life burial, vehicular pollution has seeped into our waterways causing concern for stormwater catchments in high density urban centres. The oil used was extracted from the artists car after 20,000km of driving, being entirely aware and complicit in the system.

The viscous, rich qualities of sump oil embody all that water is not. Oil drowns the oxygen in the water below, resting in the vessel as two discreet liquids. What is the future of our ecological systems when these liquids co-exist?

This project is co-produced by the City of Melbourne and Testing Grounds, and curated by Arie Rain Glorie as part of Test Sites Phase 2. Channel is presented as part of ACCA’s (The Australian Centre of Contemporary Art) program Who’s Afraid of Public Space, which explores the role of public culture, the contested nature of public space, and the character and composition of public life.

Exhibition design by Sibling Architecture.

Sculpture

Gold coin, peer-to-peer servers

2021

The collectable coin presented here was forged at the Perth Mint, a key filming location in Aurum. Inscribed on the coin is the unique contract address linked to a virtual NFT marketplace, where an edition of Aurum has been minted. An NFT (Non Fungible Token) attaches a unique code to a digital artwork using blockchain algorithms making it collectible and scarce. These decentralised crypto networks promise new models of production and trade, and with that new forms of speculation and investment. As we mine deeper into the virtual realm server farms may entirely replace the gold in vaults as stores of wealth.

National Gallery of Victoria, August 2021 - February 2022

Media link: NGV

HD Video 4:3. Archival film footage

2022

‘Every day I unbury—I dig up. I find relics of myself in the sand that women made thousands of years ago’ exclaims Louis in ‘The Waves’ (1931) by Virginia Woolf.

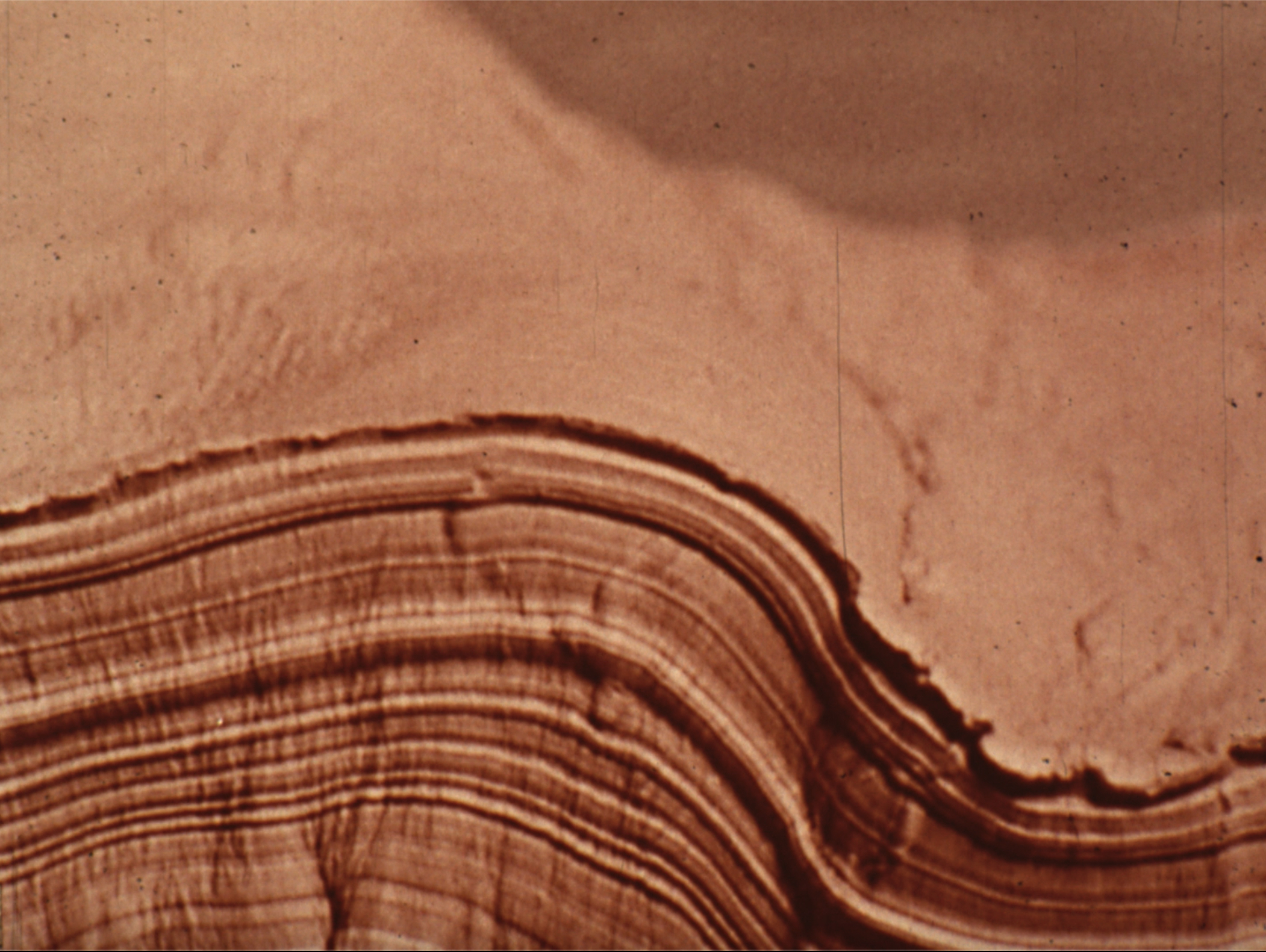

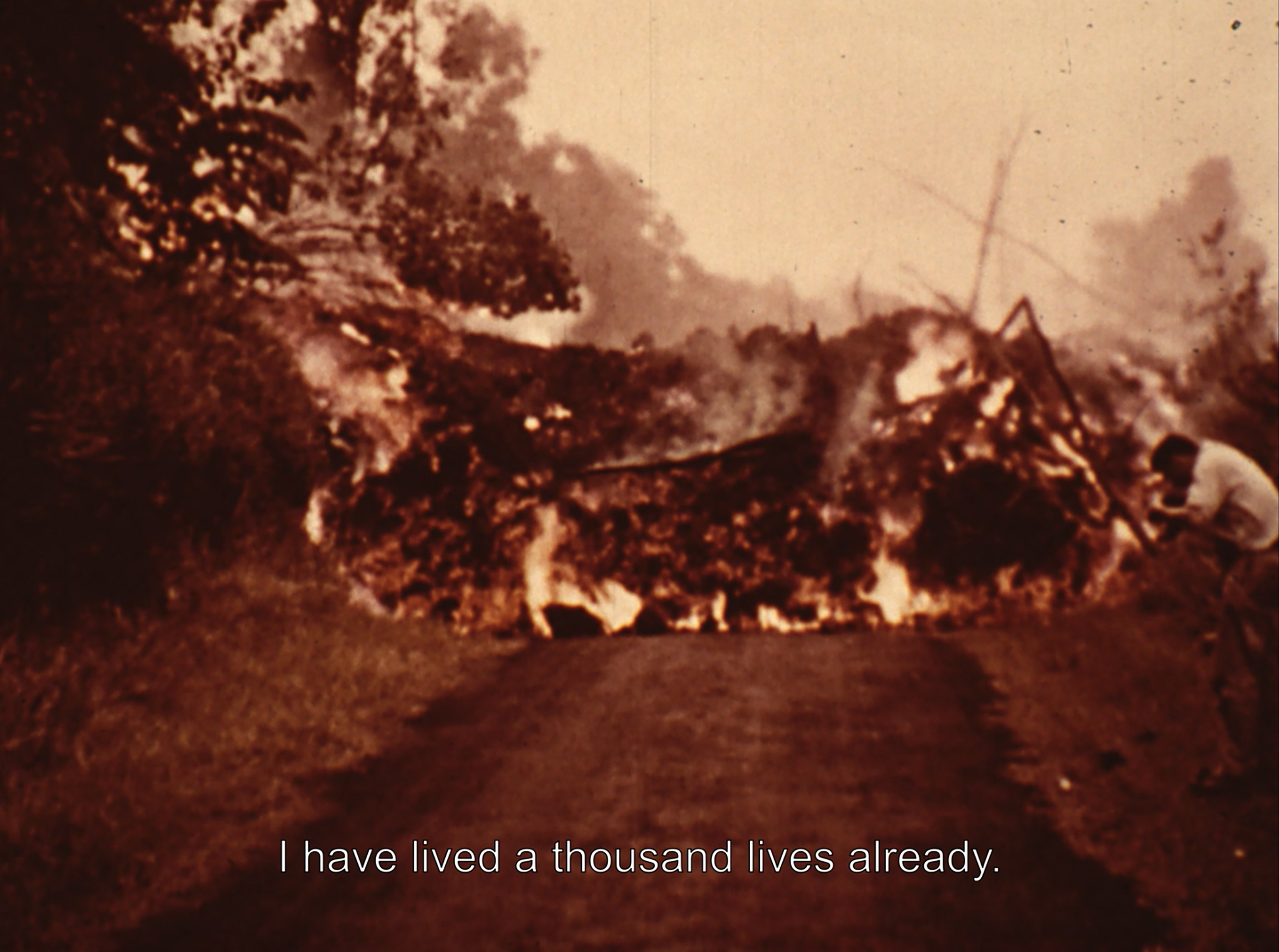

This narrative is repositioned as more-than-human, memories and musings of basaltic flows formed as part of volcanic activity thousands of years ago.

This work is part of ongoing research by Georgia Nowak & Eugene Perepletchikov into historical narratives stored in material and landscape. Fundamental to Victoria’s land and identity, the genealogy of basalt reveals a slow evolution - material becomes process within a mesh of geological and social systems.

The rhythms and ruptures of rock are animated by networks of energy flows. Like memory, material is coded through the movement of time, modulated and reconfigured, a restless sedimentation and flux that pulses through land and bodies, all entangled, never still.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

This work is part of ongoing research by Georgia Nowak & Eugene Perepletchikov into historical narratives stored in material and landscape. Fundamental to Victoria’s land and identity, the genealogy of basalt reveals a slow evolution - material becomes process within a mesh of geological and social systems.

The rhythms and ruptures of rock are animated by networks of energy flows. Like memory, material is coded through the movement of time, modulated and reconfigured, a restless sedimentation and flux that pulses through land and bodies, all entangled, never still.

ACMI Collections, Found Footage